housekeeping

Hello! Welcome to Freakazoid. I’m Bee! You probably know that already. This newsletter is a collage of things made by cool people. Each week, I’ll feature 1-4 pieces of my friends’ work, as well as one piece of my own. Medium and genre don’t matter—what matters is that whoever made it thinks it’s worth sharing. Interested in contributing something? Shoot me a DM on instagram @beehylandauthor and we’ll talk!

This week, we have some thoughts on Mondrian and a necromancy scene. Enjoy!

space-determination: what lies between “something” and “nothing”?

from raven sato

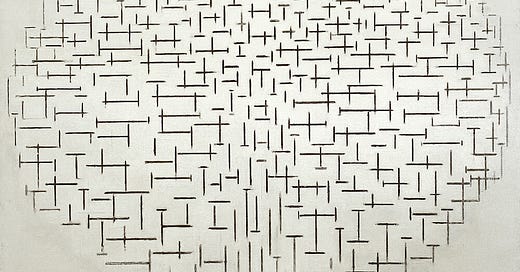

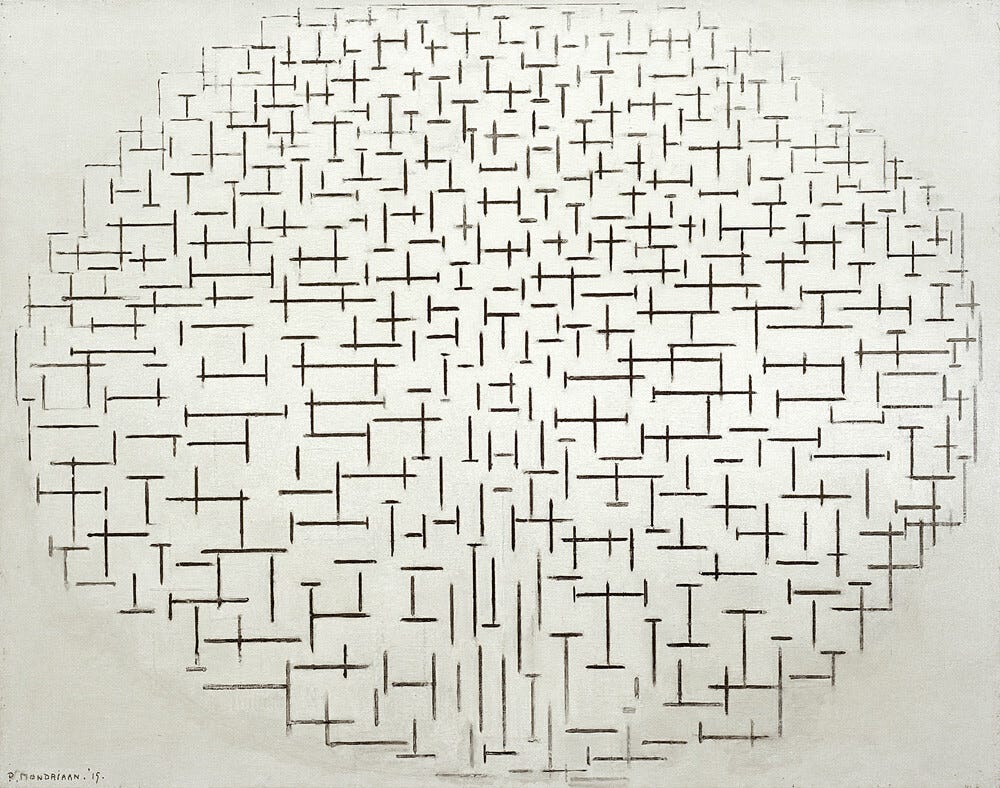

In “The De Stijl Concept of Space”, art historian Hans L.C. Jaffé remarks that the Dutch landscape is one composed of lines and right angles, as opposed to the organic curves one might expect from nature (10). The Netherlands, a country with unusually low land elevation below sea level, has always been shaped by human-made structures. While some might interpret that the straight lines of the roads and seawalls of Mondrian’s homeland served as the subject matter in works such as Composition 10 in Black and White (Pier and Ocean) (fig. 1), Jaffé cites Mondrian’s concept of space-determination to posit that the work is rather a reflection of the “human spirit” which shaped the landscape (10). I aim to take this analysis further by comparing Mondrian’s work with Aleksandr Rodchenko’s Oval Hanging Spatial Construction 12 (fig. 2). While Composition 10 utilizes the form of a grid to ultimately reflect the “human spirit”, Construction 12 takes the form of an orbital sphere to effectively communicate the mode of construction and utility behind it. However, both of these works derive meaning from relation to multidimensional space and by spatial determination. They are not works which depict space, rather they are works that reflect the principles of space. Both these modern works, one a grid composition and one an oval construction, create meaning not by what they spatially express, but by how they have been spatially determined.

Fig. 1. Piet Mondrian, Composition 10 in Black and White (Pier and Ocean), 1915

Fig. 2. Aleksandr Rodchenko, Oval Hanging Spatial Construction 12, 1920

Space-determination is a concept found in Mondrian’s essay, “The New Realism” in which he examines how abstract artforms are the “clearer expression of intrinsic reality” by being “more objective” (346). This objectivity is reached via the “reciprocal action of determined forms and determined space”, where forms and spaces are initially separated into their own distinct characters (346-347). Spaces are to be understood as the in-between or “nothing” that exists between forms, while forms carry the same connotation as “subject” or “presence” would. This distinction between form and space (as well as colour) is understood as plasticity or Plastic art. Spaces and forms, in Mondians eyes, exist in equilibrium with each other and where they meet, “intrinsic life” is expressed (347). Where space is not, form is. Where form is not, space is. They perfectly and precisely contend with each other to create our reality. The tension between the two separate, determined concepts leads to a dynamic that evokes a “universal emotion”. This universality of emotion and human experience is thus, an objective and new realism that cannot be articulated in non-plastic methods. To put it precisely, space-determination is the breaking up of empty space with forms, in reality and in art. In Piet Mondrian’s own words, “The action of plastic art is not space-expression but complete space-determination. Through equivalent opposition of form and space, it manifests reality as pure vitality.” (348).

As a concept, space-determination is significant in that it seeks to rationalize not only art but reality itself. Real world locations and their significance in culture can be understood with the vitality that is brought forth by space-determination. While living in New York, Mondrian wrote, “The metropolis reveals itself as imperfect but concrete space-determination. It is the expression of modern life. It produced Abstract Art: the establishment of the splendor of dynamic movement.” (348). The rhythm and gridlike composition in later Neoplastic works such as Broadway Boogie Woogie (fig. 3) reflect this sentiment, where the lines and squares break up the white background. One can imagine that the forms are a representation of people, cars, and roadways while the spaces are the blocks and foundations of the city, the two sections coming into contact with each other to create an unmistakable energy. The new realistic representation of the city is possible because the “grid is a staircase to the Universal”, the energy of the city is more true than its imagery (Krauss 52). A work which objectively reflects New York City, must be spatially determined precisely because the real location is also spatially determined.

Fig. 3. Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1943

Rewinding back to the beginning of the First World War, Mondrian was living in the Netherlands when he began painting his first work using only black and white. Composition 10 in Black and White (Pier and Ocean) is an oil painting on canvas measuring 110 cm by 85 cm. The base of the composition is a solidly painted warm tone of white, with some subtle inconsistencies in application. The ellipse in the centre is wider than it is tall, however while it touches the top and bottom of the canvas it does not reach the sides of the canvas. The ellipse’s base colour is a slightly more pure white than the borders of the canvas, creating a distinction between the inner main composition and the outer frame. The ellipse is filled with straight black lines, varying in length, painted strictly vertical or horizontal to the picture plane. Most of the lines cross each other to create right angles, some lines are crossed multiple times. The positioning and crossing of the lines in space appear at a glance to be arbitrary, but one may pick up on a few patterns. For example, lines at the edge of the ellipse are measurably shorter than lines near the centre and lines in the middle of the composition have longer vertical lines in closer proximity, creating a visual divide down the middle. While it is not mathematically even, the composition has a gridlike tendency due to the rigid quality of the lines and the right angles.

The composition of the lines in Composition 10, have an illusionistic way in which it implies motion and rhythm throughout. Lines in close proximity to each other appear to merge together and create a broader “wave” of forms. In viewing this piece for longer periods of time and tracking different sections of the plane with the eye, more “waves” seem to emerge from various groupings of lines. A subtle liveliness is present in the ways lines seem to illusionistically move to group with others, in both the vertical and horizontal axis. One may find it difficult to hold the eye on one single line, as the tangents of other lines draw attention away. In attempting to hold my focus on one single crossed section, it felt natural to drift my gaze to the next closest line and continue down that “wave” until another struck. For such a geometric composition, the placement of straight lines and right angles invokes a smooth, lively motion.

In the grid of this work we are able to see space-determination taking place. The white of the ellipse acts as the space while the black lines are the forms which break up and determine the emptiness. Reading it this way explains the liveliness of the composition. The tension between the forms and the space produce a motion which is easy to get swept up in. The white is not just a backdrop for the lines, it is an in-between that presses back against the lines. They are equivalent in this way, neither overtaking the other in importance. The illusory motion of the “waves” can be understood as the result of space-determination and the “intrinsic life” it evokes. It is evident, of course, in the title of the work that Composition 10 (Pier and Ocean) was inspired by and is a reflection of an ocean setting. The movement of waves can be perceived not through a pictorial depiction of an ocean but by the contention between lines and white space.

In his article, Jaffé closely examines Mondrian’s writing, citing space-determination to argue that the grid-like composition is a true reflection of “the human spirit, the constant rationality of man which triumphs here too over (...) nature.” (10). Jaffé asserts that although Mondrian writes about the Dutch landscape as a source of inspiration for his early works, such as Composition 10, it is not to be misinterpreted as the subject matter. Instead, he finds it impossible that “[Mondrian] would have perpetuated such camouflaged naturalism” (Jaffé 10). The straight lines and right angles which make up the composition are the same principles with which the Dutch landscape itself is built upon. The roads, fields, and canals of the Dutch land is, according to Jaffé, “the work of men” or in other words, the will of the human spirit (10). Rather than naturalistically represent the pier and ocean before him, Mondrian represents the determination of the people who built it via the literal determination of space. Structures built in and around Dutch waterways in particular are demonstrations of space-determination according to Jaffé. The Netherlands’ geography has always existed in contention with the ocean, pushing right up against each other. This has led to generations of Dutch people building precise structures for holding the water back (Jaffé 10). The pattern of straight line and right angle cutting through space, or rather the precision of it “have become an inheritance of the Dutch people” (Jaffé 10). Shaping the land in the name of survival is, to put poetically, replacing the curved silhouette of nature with the straight line of the human spirit. Thus, the subject matter of Composition 10 in Black and White (Pier and Ocean) is not a visual representation of the landscape but rather a reflection of the vitality and spirit of the Dutch people.

Oval Hanging Spatial Construction 12 is a work that is near impossible to describe without revealing the method of its construction. It is a sculpture with a lightweight and airy build made of thin plywood, measuring 61 by 83.7 by 47 cm when expanded. It has approximately thirteen thin, concentric rings which slot within the next bigger ring, recalling the design of nesting dolls. The rings are attached via thin wire, which allows it to be expanded into a 3D spherical, orbital structure as well as folded up into a flat 2D circular plane. It can be hung with a wire attached to the outermost ring, allowing it to be suspended while expanded. One side of Spatial Construction is left the untainted colour of the plywood while the other is painted in a silver aluminium paint, said to “catch the light” with its metallic quality (Gough 96). Due to its lightweight and multi-positional construction, it is a mobile piece in more ways than one. While suspended, it is rarely a static piece rather “the slightest variation in air current [set] Rodchenko’s delicate ellipse into motion” (Gough 96). Moreover, the piece is so lightweight and portable that it can be easily transported or archived. Oval Hanging Spatial Construction 12 is a piece which invokes a strong impression of design and industrial construction.

The early work of Rodchenko and other Constructivist artists was fixated on the nature of construction and industrial production as art. In a series of debates, the First Working Group of Constructivists found their way to a definition of the movement in two parts: the faktura or material qualities of a piece and the tektonika or spatial presence of a piece. As part of the beginning discussions among the group was a debate on how constructions differ from compositions exactly (Gough 39). Each member had a differing stance, but Rodchenko’s philosophy could be described as “utilitarian”. The true constructive work, according to Rodchenko, is one where “the existence of a purpose or goal [is present] in the organization of a work’s elements and materials.” (Gough 47). The faktura of a given work must have a utility of some kind to be deemed a construction. Furthermore, the utility of the elements must be evident to the observer – they must be able to understand how the construction “works” at a glance. Only by “negating decorative elements” could one focus on the material and spatial presence of a construction (Gough 49).

Aleksandr Rodchenko’s Spatial Construction 12 is a demonstration of his utilitarian stance. The materials and process of the work are laid bare to the spectator, as are the utility of each element. The nesting rings, by their very nature, inform the viewer that they were cut from the same wood panel. The wiring of the rings are organized in such a way that their utilitarian purpose, to allow movement or suspend the construction, are evident. Moreover, the natural movement of the delicate piece when it is spun by wind demonstrates its function and the function of the individual elements. The simplicity of its form and the limited range of materials are effective in that, with a glance, any worker could recreate this construction for themselves as an industrial art object. Finally, its utility as a collapsible object fit for travel distinguishes it from composition further. As its spatial presence shifts, its purpose shifts from that of a displayed art object to that of a discrete, archived item. While a composition such as Mondrian’s Composition 10 is capable of being packed up for travel, it was not created with that utility nor is that utility evident in the piece alone. The visible multipurpose of Spatial Construction 12, clearly both a displayable object and an archivable object, means that it is a true constructive work in the eyes of Rodchenko.

Applying Mondrian’s concept of space-determination to a reading of Rodchenko’s Spatial Construction 12 adds another layer to its interpretation. The Constructivist understanding of tektonika bears some similarity to space-determination. To the First Working Group of Constructivists, the series of Spatial Constructions “advances space itself – “empty” space –as “concrete” material. (...) It orchestrates this material but does not fill it. (...) It asserts itself as distinct not only from traditional forms of relief and monument, but also from the abstract forms” (Gough 66). Here we can see a commonality to space-determination where space and form are considered distinct elements. Furthermore, space is viewed not as a lack of presence, but as a concrete material which orchestrates or has an effect on form. In Spatial Construction 12, it can be understood that the determined forms are the rings and the determined space is the empty air of the room occupying the space between its expanded rings. In this way, the constructed forms of the work break up the space of the room it is displayed in. As a three-dimensional piece, Spatial Construction 12 does more than reflect a spatially determined location, it is in reality the spatially determined location itself. Furthermore, due to its airy construction it invokes “intrinsic life” and motion as it reacts to wind and movement. The effect of spatial-determination in Composition 10 is the wave-like dynamic expressed in the black lines and white space. In Spatial Construction 12, the effect is the swaying and spinning dynamic as the wooden rings and air of the room come into contact with each other. The movement in both invokes the “intrinsic life” and vitality that Mondrian argues is the “real content of art” (Mondrian 348).

In contrast, the form of each work is completely different. A geometric grid in one and a spherical oval in the other. While both contend with space, the shape is what sets the interpretation of each piece apart. To mondrian, curved forms are too naturalistic and thus not plastic enough to represent true objectivity. Straight lines and right angles are necessary in order to determine the space of the grid. To show objectivity and thus, the “human spirit”, the line and right angle are the necessary form. To Rodchenko, the spherical nature of the hanging construction is important to understanding its construction. A closed off, solid form would not adequately communicate the way of its making. Additionally, it would not be as portable due to size and weight, defeating one of its utilities. The ideal form fit for construction is the oval and the sphere existing in space.

Despite the divergence in shape of form, Piet Mondrian’s Composition 10 in Black and White (Pier and Ocean) and Aleksandr Rodchenko’s Oval Hanging Spatial Construction 12 derive meaning from their contention with space. The spatially determined reality of waterways in the Netherlands as well as the enduring “human spirit” which built it are reflected in the spatially determined grid of Composition 10. The new reality of the world is deemed present in the vitality of movement in the work. The space which orchestrates the motion of Rodchenko’s Spatial Construction 10, adds complexity to its utility as a constructivist object. Its form finds purpose, a requirement of Rodchenko’s utilitarian Constructivist argument, by determining the space around it.

Works Cited

Gough, Maria. The Artist as Producer: Russian Constructivism in Revolution. University of California Press, 2005.

Jaffé, Hans Ludwig C. De Stijl. H. N. Abrams, 1971.

Jaffé, Hans Ludwig C. “THE DE STIJL CONCEPT OF SPACE.” The Structurist; Saskatoon, vol. 0, no. 8, 1968, pp. 8-12. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/de-stijl-concept-space/docview/1297874329/se-2?accountid=14656.

Krauss, Rosalind. “Grids.” October, vol. 9, 1979, pp. 51-64. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/778321.

Mondrian, Piet. Broadway Boogie Woogie. 1942-43. Oil on canvas. Museum of Modern Art, United States.

Mondrian, Piet. Composition 10 in Black and White (Pier and Ocean). 1915. Oil on canvas. Kröller-Müller Museum, Netherlands.

Mondrian, Piet. The New Art--the New Life: The Collected Writings of Piet Mondrian. Edited by Harry Holtzman and Martin S. James, translated by Harry Holtzman and Martin S. James, G.K. Hall, 1986.

Mondrian, Piet. Plastic Art and Pure Plastic Art, 1937, and Other Essays, 1941-1943 [by] Piet Mondrian. New York (State), Wittenborn and company, 1951, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015013643815. Accessed 11 December 2022.

Rodchenko, Aleksandr. Oval Hanging Spatial Construction 12. 1920. Plywood, open construction partially painted with aluminum paint, and wire. Museum of Modern Art, United States.

Raven Sato (they/she/he) is an artist and curator based in Vancouver, British Columbia. They should really practice their DJ set instead of spending all their time engaging with historic and contemporary artworks that challenge hierarchical spaces.

the undying scene

from me

At first, Aaron had thought it was a joke. Not a very funny or tactful joke, but Iamb often struggled with humor and tact. But this was the exact sort of shit she would laugh maniacally about when they were kids high off whatever they had gotten their hands on that week.

But no, Iamb was dead serious about this. Her eyes twitched; her pupils were pinpricks. She hadn’t slept in days, probably had barely eaten. But she gripped Aaron’s shoulder and she said, plainly despite the bruises her fingers were bound to leave on him, “I’m going to get my sister back.”

She didn’t ask him if he would help. The two of them both knew that he didn’t have another option.

Epi had died messily. Resurrection was nigh impossible–the few reported cases had been on clean, simple deaths–common poisons, bleeding out, aneurysm. Aaron would not have remembered a clean death anywhere near as well as he remembered the way Epi spent her last days–infection spreading through her body, eating away at her flesh; medics and healers alike hovered over her body throwing out hypothetical cures that only made things worse. Iamb had been there, tiny and quiet in the corner of the ward while Aaron got up close.

Aaron explained this to Iamb.

She had responded curtly, “That doesn’t matter. I’m going to bring her back.” After another pause, she hummed. “Do you have a shovel?”

The coffin had been cheap, and it was already rotted through a bit. Epi’s body–dressed nicely, still, though the embroidered robes were a bit maggot-chewed–was visible without even having to put in the effort to lift the lid. Aaron still made the effort.

“So, what next?” he asked. Iamb had been more vague than usual, and Aaron–well, Aaron was used to this sort of thing. He knew the temperaments of mages well by this point. The temperaments of Iamb specifically, he knew especially well. So long as he held some level of faith in her, he was fairly sure he could hold himself off from obsessing over his best friend’s corpse; he could just drift off and trust Iamb.

But he still needed to know a plan, or else drifting off would be impossible.

Iamb was silent, staring at Epi’s still-open eyes. They were glassy, but still their old dark selves.

“What next?” Aaron repeated, softer.

Iamb put a hand to Epi’s still chest and just whimpered, collapsing over the body, and she cried out, “Please,” with a sort of desperate hunger Aaron had never heard from her before. “Please.”

And there were corners of him that wanted to scream at her–you dig up your sister’s corpse just to ask her to live again, as if that will do anything. And those corners yelled and yelled and yelled.

And there was a corner that saw Epi’s jaw twitch.

a song for your week

One of my favorite songs from last year, Turkey Vultures by Wednesday!

Have a great week!